What is Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy?

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a genetic disorder characterized by the progressive loss of muscle. It is a multi-systemic condition, affecting many parts of the body, which results in deterioration of the skeletal, heart, and lung muscles.

Duchenne affects approximately 1 out of every 5,000 live male births. About 20,000 children are diagnosed with Duchenne globally each year.

Duchenne is caused by a change in the dystrophin gene. Without dystrophin, muscles are not able to function or repair themselves properly. Becker muscular dystrophy, which can be slower progressing than Duchenne, occurs when dystrophin is made, but not in the normal form or amount.

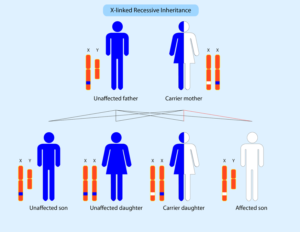

Because the dystrophin gene is found on the X-chromosome, it primarily affects males, while females are typically carriers. However, females can manifest varying ranges of symptoms of Duchenne, and if so may be called “manifesting carriers”.

You may hear the term “dystrophinopathy” which refers to the spectrum including Duchenne, Becker, and manifesting carriers. PPMD’s mission and work extends to Duchenne,Becker, & carriers, but for simplicity we primarily refer to Duchenne.

What causes Duchenne?

Duchenne is caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes for dystrophin, a protein that is essential to the proper functioning of our muscles. Without dystrophin, muscles are not able to function or repair themselves properly. The loss of muscle then results in a loss of strength and function.

Duchenne can be passed from parent to child, or it can be the result of random spontaneous genetic change, which may occur during any pregnancy. In fact, about one out of every three cases occurs in families with no previous history of Duchenne. In other words, it can affect anyone, and crosses all races and cultures. Learn more about what causes Duchenne and Becker and how it can affect more than one person in a family.

Learn about Genetic CausesWhat are signs and symptoms of Duchenne?

The average age of a Duchenne diagnosis is around 4 years old. Many times there will be delays in early developmental milestones such as sitting, walking, and/or talking. Speech delay and/or the inability to keep up with peers will often be the first signs of the disorder. The symptoms of Becker can begin in childhood, the teenage years, or even later. Learn more about the signs and symptoms of Duchenne

Learn about Signs and SymptomsWhat is the progression of Duchenne?

Duchenne progresses differently for every person. Even siblings with the same genetic variants may have a different progression of symptoms.

Muscle loss is first noticed in childhood, with loss of strength, function, and flexibility in the hips, thighs, shoulders, and pelvis. In the teens, these losses begin progressing to the arms, lower legs, and trunk. Because there is also an absence of dystrophin in the muscles of the heart and lungs, heart function and breathing are also affected. In addition, some people can have issues with learning and behavior, resulting from a lack of dystrophin in the brain.

The progression of symptoms through Duchenne are on a spectrum, from late onset/very mild symptoms to early onset/severe symptoms. Regular visits with your neuromuscular team will help you to monitor the progression of this condition, and how it can best be treated along the way. Learn more about how Duchenne progresses.

Learn about ProgressionWhat is the average lifespan of Duchenne?

With improved care, more people with Duchenne are living into their early 30s and beyond. With clinical care continuing to improve, as well as clinical trials, research, and therapies on the horizon, we are hoping to enhance both the quality and quantity of life with Duchenne to a much older age.

While there is no cure yet for Duchenne, and many parents are told that there is no hope and little help, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy exists to offer the support and resources parents may not find anywhere else. There is hope — with more than 40 companies currently working on treatments for Duchenne and more than 20 drugs in clinical trials, there are tremendous reasons to hope. Knowledge is power, and informed and timely care can help people living with Duchenne live longer and with a much greater quality of life than ever before.

Why is it important to know your specific Duchenne variant?

Many therapies in development and/or approved for Duchenne are “variant-specific”, meaning they will only benefit individuals with certain genetic variants. You must know your genetic variant in order to participate in clinical trials and to access current or future variant-specific therapies. If you’ve never had genetic testing or if you need repeat genetic testing, PPMD is able to provide free genetic testing to eligible individuals through our Decode Duchenne program.

Learn about Types of VariantsWhat does it mean to be a carrier?

A carrier is a woman who has a change in one of her two copies of the dystrophin gene. Carriers have an increased chance of having sons with Duchenne and daughters who are carriers.

Females carriers are usually not diagnosed with Duchenne or Becker because they make enough of the dystrophin protein. However, they can have a range of symptoms related to dystrophinopathy, such as muscle weakness and heart problems. Though it is rare, some females can have the classic symptoms of Duchenne. All carriers should be checked by a healthcare provider familiar with Duchenne, including a cardiologist. Learn more about what it means to be a carrier.

Learn about CarriersWhat if you are not sure your child has Duchenne?

Having an accurate, timely diagnosis is a critical aspect of care. There are several tools that you and your primary care provider can use to evaluate your child:

- For Parents: The American Academy of Pediatrics has developed the Physical Developmental Delays: What To Look For tool to help parents evaluate their child’s physical development, and possible delays.

- For Medical Providers: ChildMuscleWeakness.org is a site that can be shared with medical professionals in order to help them evaluate their patients for delays and possible diagnoses.

- Confirming the Diagnosis: PPMD is able to provide free genetic testing to eligible individuals through our Decode Duchenne genetic testing program. The application and testing process is fast and easy. Learn more about PPMD’s free genetic testing program.

Learn more about the signs of Duchenne and how it is diagnosed.

Learn about DiagnosisWhat is the current status of care and treatment for Duchenne?

While there is currently no cure for Duchenne, there is hope – perhaps more now than ever before. PPMD has been at the forefront of advancements in care and treatments for Duchenne. We take a cutting-edge approach to accelerate finding treatments that will end Duchenne for every single person impacted by the disease.

Improvements in care

We’ve seen the greatest advancements in the fight to end Duchenne around standards of care, resulting in greatly improved quantity and quality of life. Because of PPMD’s push to advance care, people with Duchenne are living longer, stronger, happier, more productive lives. Our community members hold important jobs, impact policies in Washington, get married and raise families – things many thought were impossible even 10 years ago.

Advances in research and treatments

PPMD has invested more than $50 million into innovative research that will make an impact across the disease, no matter the mutation, age, or stage of progression, including investments in strategies and therapies that restore or replace dystrophin (for example, gene therapy, exon skipping, CRISPR, etc.), as well as those that treat the symptoms (for example, those that target fibrosis, inflammation, blood flow, etc.), knowing that a treatment for Duchenne will likely take a combination of therapies.

Since 2016, the FDA has approved several treatments in Duchenne with additional therapies approaching the regulatory finish line.

For more questions, please reach out to PPMD’s Care Team careteam@parentprojectmd.org or schedule a 1:1 meeting with members of our team here