Genetic Causes

Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy are caused by changes in a single gene in our bodies. Duchenne and Becker can be passed from parent to child, or it can be the result of a new, spontaneous genetic variant, which can occur during any pregnancy. In fact, about one out of every three cases of Duchenne occurs in families with no previous history of Duchenne.

What is the role of dystrophin?

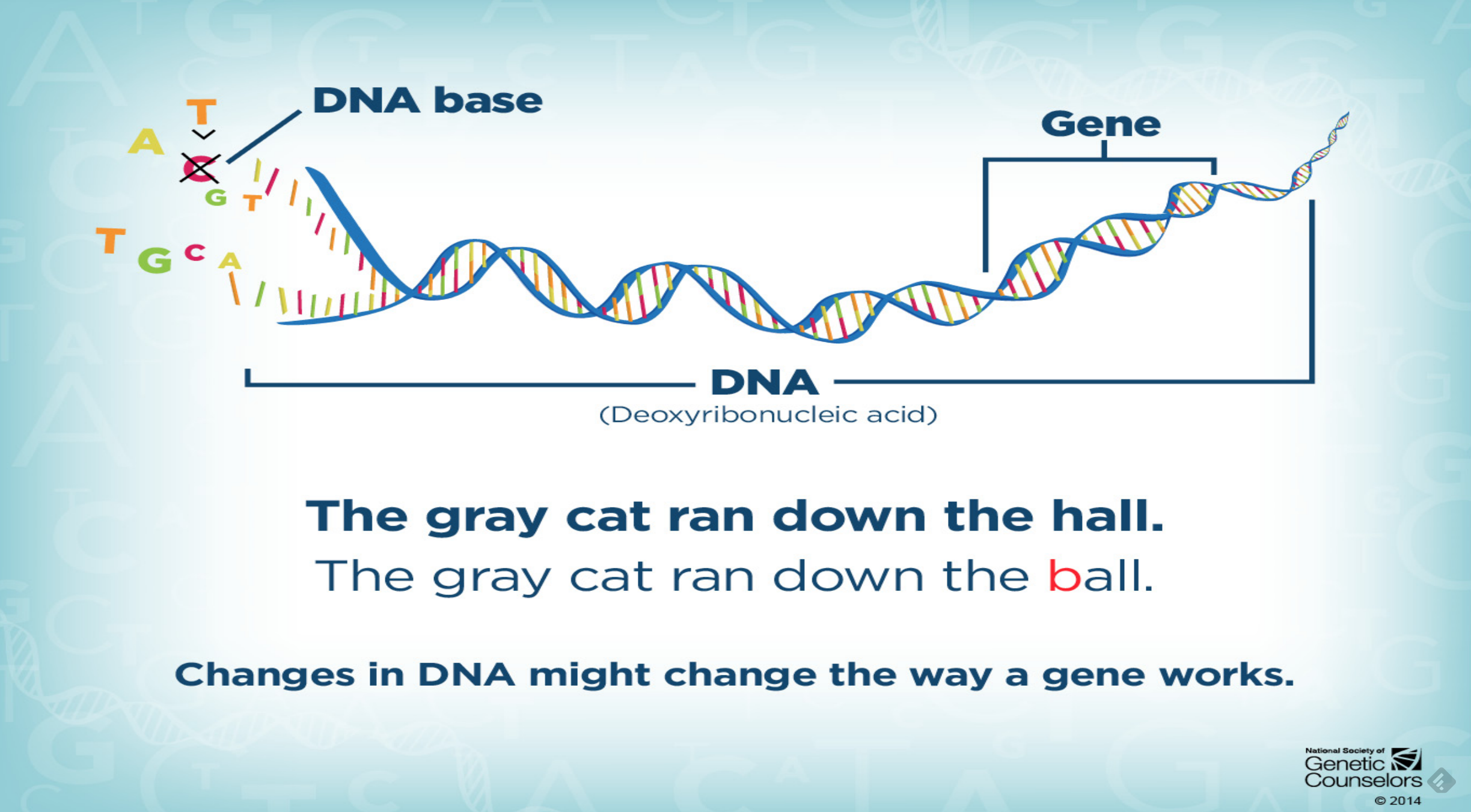

Duchenne and Becker,also known as dystrophinopathies, are caused by a change in the DMD gene. Genes are small pieces of DNA that contain the instructions for how to make a protein, which is a type of molecule. The DMD gene is basically a recipe for how to make the dystrophin protein.

The dystrophin protein is critical for maintaining muscle cell structure and function. Dystrophin acts as a “shock absorber” that allows muscles to contract and relax without being damaged.

Without dystrophin, muscles are not able to function or repair themselves properly. The muscle membrane is easily damaged by normal day to day activity, creating tiny micro tears in the cell membrane. These tiny tears let calcium come into the cell, which is a toxic substance to muscle. The calcium damage eventually kills the muscle cells, allowing them to be replaced with scar tissue and fat. In turn, the loss of muscle results in a loss of strength and function.

Changes to the gene, called variants, can lead to differences in the amount, size, or function of the dystrophin protein. Duchenne and Becker occur because there is not enough functional dystrophin protein in the muscle cells. Some types of variants in the DMD gene, such as those that lead to essentially no dystrophin production, are more commonly associated with Duchenne. Other types of variants are more commonly associated with Becker, although many variants can have variable symptoms ranging from mild to severe.

How are Duchenne and Becker inherited?

In order to understand how Duchenne or Becker can occur in a family, it is helpful to understand some basic genetics. We as humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, or 46 total, in every cell of our body:

- 44 autosomes (pairs 1-22)

- Every child inherits one copy of each autosome from each parent

- 2 sex chromosomes (pair 23)

- Females usually have two X chromosomes (XX), one from each parent

- Males usually have one X and one Y chromosome (XY), the X chromosome from their mother and the Y chromosome from their father

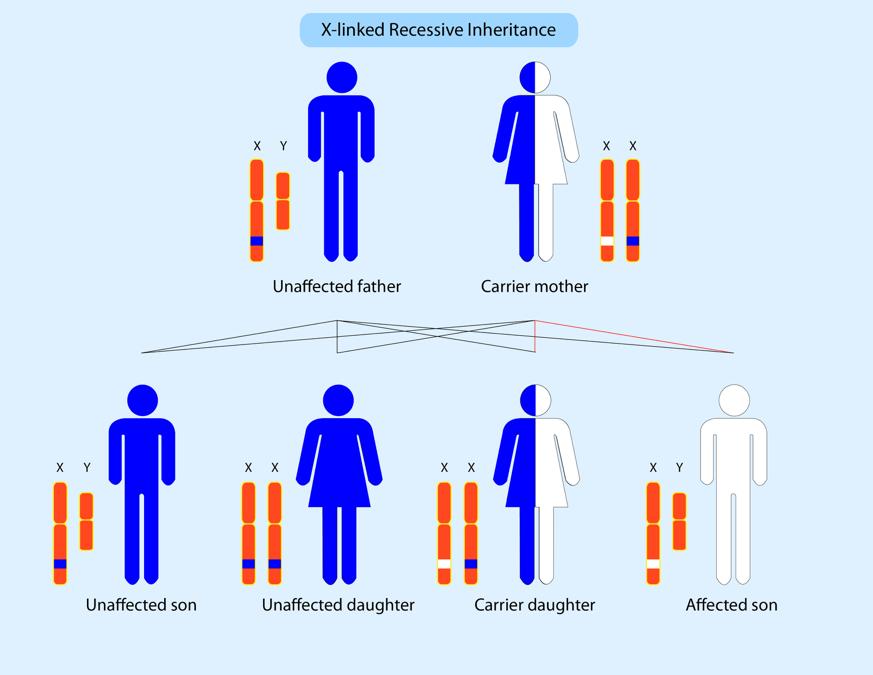

The DMD gene is located on the X chromosome, which is why Duchenne and Becker primarily affect males. When females inherit a DMD gene variant, they typically have a second X chromosome and second copy of the DMD gene to serve as a “backup”. Males typically only have one X chromosome, so if they have a DMD gene variant, there is no backup to provide fully functional dystrophin protein.

Because DMD gene variants are on the X chromosome, Duchenne and Becker are considered “X-linked” conditions and have X-linked inheritance.

If a female carries a variant on one copy of her two DMD genes, with each pregnancy she will have a 50% chance of passing on the copy of the gene with the variant. Carriers have no control over which copy of their X chromosome they pass on to their children when conceiving naturally.

- Each time a carrier woman has a son, there is a 50% chance (or 1 out of 2) that he will inherit the variant and have dystrophinopathy.

- Each time a carrier woman has a daughter, there is a 50% chance (or 1 out of 2) that she will inherit the variant and be a carrier, and also may develop symptoms of dystrophinopathy.

If a woman carries a mutation in the gene that encodes for her dystrophin, with each pregnancy she will have a 50% chance of passing on the gene with the mutation.

- Each time a carrier woman has a son, there is a 50% chance (or 1 out of 2) that he will be affected with Duchenne.

- Each time a carrier woman has a daughter, there is a 50% chance (or 1 out of 2) that she will be a carrier or a manifesting carrier.

Carriers have no control over which copy of their X chromosome they pass on to their children.

Duchenne can also occur without being passed from parent to child, as the result of random spontaneous genetic mutations, which may occur during any pregnancy. About 1 out of every 3 cases occurs in families with no previous history of Duchenne. In other words, it can affect anyone, and crosses all races and cultures.

Males with dystrophinopathy pass on their X chromosome with the variant to each of their daughters, and their Y chromosome to each of their sons. This means that none of their sons are expected to have dystrophinopathy, but all of their daughters are expected to be carriers and may or may not develop symptoms.

Duchenne and Becker can also occur without being passed from parent to child, as the result of random spontaneous genetic variants, which can occur during any pregnancy.

Where do DMD gene variants come from?

The DMD gene, like any gene in our body, can develop changes by random chance. Thousands of different variants have been reported in the dystrophin gene. It is important to keep in mind that no one causes gene variants, and they cannot be prevented. Each of us carries variants in some of our genes, though we usually do not know it.

For children with dystrophinopathy, their DMD variant gene variant typically occurred in one of three ways:

- The variant has been in the family for a long time

The variant was inherited from a parent, most commonly a female carrier who did not have noticeable symptoms. The variant may have been passed through many generations in the family without knowing it was there, especially if it was never inherited by a male child. - The variant is new in the child’s parent

The variant was not passed through generations of the family. Instead, a new (de novo) genetic change occurred by chance in the egg, sperm, or embryo that developed into the mother. The mother is a carrier (often without knowing it) and when she has a son, she randomly passes on her copy of the DMD gene that has the variant. Less commonly, the mother has a new genetic change that developed only in her egg cells, called germline mosaicism. When this happens, the mother is not considered a carrier at risk of symptoms, but there is a chance she passes on the DMD variant to more than one child. - The variant is new in the child

The variant was not passed through generations of the family or inherited from a parent. Instead, a new (de novo) genetic change occurred by chance in the egg or embryo that developed into the affected child. The variant is not present in the mother and she is not a carrier.- About 1 in 3 (33%) cases of Duchenne occur this way.

- About 1 in 10 (10%) of Becker cases occur this way.

Because DMD variants can develop randomly, dystrophinopathy can affect anyone, and crosses all races and cultures.